1863 Letter by Private J. Tilden Moulton, 33rd Illinois — Separated from Regt during May 22 Assault at Vicksburg — Rebels "tried to hurt us with buck shot and hand grenades, but we lay snugly enough"

1863 Letter by Private J. Tilden Moulton, 33rd Illinois — Separated from Regt during May 22 Assault at Vicksburg — Rebels "tried to hurt us with buck shot and hand grenades, but we lay snugly enough"

Item No. 9265548

This June 1863 letter was written from “Before Vicksburg” by Private Jotham Tilden Moulton III of the 33rd Illinois Infantry. In it he discusses his regiment’s role in the Vicksburg campaign as well as in the May 22 assault upon Vicksburg itself. Writing to his sister Carrie, Moulton opens the letter stating that he had not had opportunity to write “since we crossed the Mississippi” in late April, as General Ulysses S. Grant’s campaign to take the Confederate river stronghold gathered steam. He continues recounting the role played by the 33rd, which served in the 13th Corps division commanded by Brigadier General Eugene A. Carr. This division led attacks at Port Gibson on May 1 and Big Black River Bridge on May 17:

I presume the papers have kept you informed of the brilliant movements in which it has been my privilege to bear a part. Carr’s division first crossed the river, first seized the narrow defile near the landing, where a comparative handful of determined men might have delayed us till their reinforcements could come up. Carr’s division opened the battle of Port Gibson, and Carr’s division gained the victory at Black River Bridge.

Moulton continues writing about the May 22 attack at Vicksburg, in which the the 33rd unsuccessfully attacked the 2nd Texas Lunette on the southern end of the Confederate works:

Carr’s division suffered more severely than any other in the unfortunate assault on May 22d, losing 845 men killed and wounded. In this last fight I missed my way in the charge and lay within the enemy’s lines all day, while the battle raged around me and shot and shell were whistling and screaming all the time over our heads. About thirty of us lay for ten hours in a little hollow, where we could not come out for fear of the enemy and the rebels could not come upon us for fear of our sharpshooters. They tried to hurt us with buck shot and hand grenades, but we lay snugly enough. The colonel of the 33d [Colonel Charles E. Lippincott] and the Lieutenant [William T.] Lyon, commanding our company, were in the same hollow, so I did not conceive myself exactly disgraced by my rather inglorious position. After dark we heard the rebels making up a party to capture us, so we sneaked off in good order, every man for himself. Some of us were shot at, but no one was hit.

He then relates the experience of a friend identified as “Frank” who reportedly had been an aide to their brigade’s commander, Brigadier General William P. Benton:

Frank was in a warm place that day, and got exercise enough to keep him warm. He is aide de camp to General Benton, and had to run back and forth upon errands a number of times under a severe fire. He took one cannon up tolerably close to the enemy’s works and kept firing through the embrasures till the place became too warm for him and the artillerymen ran away. He and one cannoneer dragged the gun back to a place of safety.

Returning to his own experience, Moulton writes that “when we were charging over the hill that day I found that my canteen was in my way and I threw it over my head and have not seen it since,” and that “all that terrible day I lay in the sun without any water.” That evening his thirst “became intolerable, and I ran about almost distracted till I found water.” He considers the loss of his canteen a “lucky accident,” however, because after finding another with a tin cup attached to it, he was delighted to trade the cup to another soldier for a cup of coffee, which refreshed him “you cannot tell how much.”

By June 5 when Moulton began writing the letter, the Army’s operations had turned to a siege:

Our present duties are rather rough. Almost every night we must work in the rifle pits, or stand guard in them, and when we sleep we cannot take off our clothes or accoutrements. We have no tents, no shelter from the rain, no shelter from the sun except such as we can make by stretching our blankets upon sticks, and that is a poor dependence when the wind blows hard. We were greatly exhausted by fighting, forced marches, exposure and privations when we arrived here, and the hard work of the siege is wearing us out at a terrible rate. Vicksburg will be taken—of that rest assured, but it will cost us many thousand lives.

Moulton continues the letter on June 7, describing how his health had deteriorated so quickly. At the beggining of the campaign he had “never felt better or stronger in my life.” But after the grueling marches in the heat and humidity, as well as several battles, he describes having “hardly strength to go to the spring for a drink of water” and was “suffering from diarrhea.” He continues:

I live out of doors and sleep exposed to all the nuisance of this most unhealthy climate. I have some boards under me, plenty of blankets, and a slight shelter overhead affording a partial protection agains the direct rays of the sun in the daytime and here I lay almost constantly when not on duty the most of the last two days, for yesterday I had no duty assigned me, and felt too weak to move about or even finish my letter. [It] has done me some good, and I expect to be on guard in the rifle pits tonight. I take no medicine, live on ordinary rations, and just take my chance of getting sick or well. If Vicksburg surrenders soon I mean to nurse myself faithfully.

Through the ordeal Moulton’s spirits remain high. He reports, “deserters by tens and twenties come over to us every night and they always are reporting a state of terrible and unceasing destruction within the walls.”

The remainder (page 4 of the letter) largely discusses personal matters, including questions about mail getting through and complimenting his sister on her improved writing skills. He states that he does not expect to return to school in Maine that fall due to the war. The faint handwriting and toned condition of this page make this portion particularly difficult to put together.

Moulton would survive the siege and would reenlist as a veteran in January 1864. He was discharged for disability in August 1865. His father J. Tilden Moulton, Jr., was a former Massachusetts and Maine attorney who had moved his family and practice to Chicago in the early 1850s, where he became one of the first editors of the Chicago Tribune and was reportedly a personal friend of Abraham Lincoln. The younger Moulton was also older brother to Lewis F. Moulton, who was a noted land baron of Southern California in the later nineteen and early twentieth centuries.

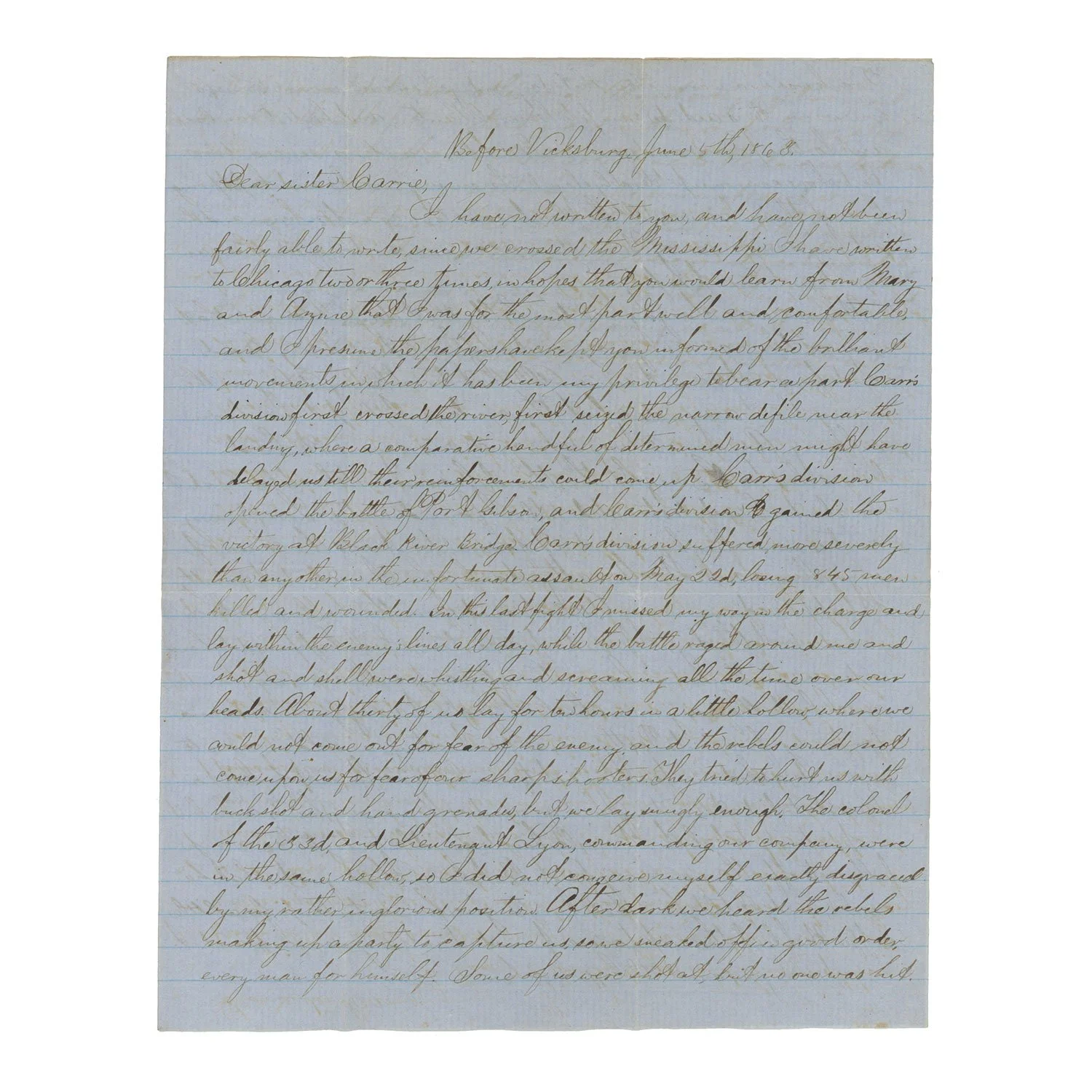

The letter was written on four pages of a 7 1/2” x 9 1/2” letter sheet. As mentioned above, there is faint handwriting on the fourth page, and then also on much of the third page as Moulton changed from writing in pen to pencil. The letter’s condition is very good other than for the toning on the fourth page, as well as some light foxing. Creased where originally folded. The partial transcript appears below:

Before Vicksburg, June 5th, 1863.

Dear sister Carrie,

I have not written to you, and have not been fairly able to write, since we crossed the Mississippi. I have written to Chicago two or three times in hopes that you would learn from Mary and Annie that I was for the most part well and comfortable, and I presume the papers have kept you informed of the brilliant movements in which it has been my privilege to bear a part. Carr’s division first crossed the river, first seized the narrow defile near the landing, where a comparative handful of determined men might have delayed us till their reinforcements could come up. Carr’s division opened the battle of Port Gibson, and Carr’s division gained the victory at Black River Bridge. Carr’s division suffered more severely than any other in the unfortunate assault on May 22d, losing 845 men killed and wounded. In this last fight I missed my way in the charge and lay within the enemy’s lines all day, while the battle raged around me and shot and shell were whistling and screaming all the time over our heads. About thirty of us lay for ten hours in a little hollow, where we could not come out for fear of the enemy and the rebels could not come upon us for fear of our sharpshooters. They tried to hurt us with buck shot and hand grenades, but we lay snugly enough. The colonel of the 33d and the Lieutenant Lyon, commanding our company, were in the same hollow, so I did not conceive myself exactly disgraced by my rather inglorious position. After dark we heard the rebels making up a party to capture us, so we sneaked off in good order, every man for himself. Some of us were shot at, but no one was hit. Frank was in a warm place that day, and got exercise enough to keep him warm. He is aide de camp to General Benton, and had to run back and forth upon errands a number of times under a severe fire. He took one cannon up tolerably close to the enemy’s works and kept firing through the embrasures till the place became too warm for him and the artillerymen ran away. He and one cannoneer dragged the gun back to a place of safety.When we were charging over the hill that day I found that my canteen was in my way and I threw it over my head and have not seen it since. All that terrible day I lay in the sun without any water, but the excitement kept me from suffering. As soon as I was safe and our regiment had bivouacked for the night the thirst became intolerable, and I ran about almost distracted till I found water. Losing my canteen was a lucky accident for me, for it was the cause of my getting a cup of coffee after dark, when I needed it greatly. It happened in this way. As I returned from the hollow in which we had spent the day, I picked up a canteen which happened to have a tin cup attached—a large, strong tin cup with a riveted handle—much better than my own, which I bought off a n___r in Louisiana for twenty-five cents. Pretty soon, as I sat resting a soldier came to me and asked me for a tin cup to drink some coffee out of. Coffee! I was electrified at the idea. I had ground coffee in my haversack, but no opportunity to boil it. It would have been idle to try to beg a cup full, or to offer the man money for it. But here I had just what he wanted, and I told him that I would give him a tin cup for a little coffee. He filled the cup for me, poured it into my new cup, and I was refreshed you cannot tell how much.

Our present duties are rather rough. Almost every night we must work in the rifle pits, or stand guard in them, and when we sleep we cannot take off our clothes or accoutrements. We have no tents, no shelter from the rain, no shelter from the sun except such as we can make by stretching our blankets upon sticks, and that is a poor dependence when the wind blows hard. We were greatly exhausted by fighting, forced marches, exposure and privations when we arrived here, and the hard work of the siege is wearing us out at a terrible rate. Vicksburg will be taken—of that rest assured, but it will cost us many thousand lives.

7th. I meant to finish this letter the same day that I began it, but I was too weak. I have been very much worn out by the toil and exposure of this campaign, and my health is very poor. When we left Ste. Genevieve I was in splendid health; never felt better or stronger my life, and I had a good share of strength left when we crossed the Mississippi. I marched upon Port Gibson. But that is all gone now. I have hardly strength to go to the spring for a drink of water, and I am suffering from diarrhea. My course of treatment is not perhaps to [illegible] or the most likely to effect a cure. I live out of doors and sleep exposed to all the nuisance of this most unhealthy climate. I have some boards under me, plenty of blankets, and a slight shelter overhead affording a partial protection agains the direct rays of the sun in the daytime and here I lay almost constantly when not on duty the most of the last two days, for yesterday I had no duty assigned me, and felt too weak to move about or even finish my letter. [It] has done me some good, and I expect to be on guard in the rifle pits tonight. I take no medicine, live on ordinary rations, and just take my chance of getting sick or well. If Vicksburg surrenders soon I mean to nurse myself faithfully. I have [illegible] must [illegible] of the capitulation of this place before [illegible] on this letter. Deserters by tens and twenties come over to us every night and they always are reporting a state of terrible and unceasing destruction within the walls.

[The remainder of the letter appearing on page 4 is very faint and only a partial transcript could be produced. Moulten discusses personal matters, commenting on letters getting through and complimenting his sister on her improved letter writing skills. He also states that it is unlikely he will return to school in Bucksport, Maine, that fall due to the war continuing. He signs the letter “brother Tilden.”]