1863 Letter by Private Julius P. Varney, 42nd Massachusetts — Pontoon Bridge Duty During Bayou Teche Campaign in Louisiana

1863 Letter by Private Julius P. Varney, 42nd Massachusetts — Pontoon Bridge Duty During Bayou Teche Campaign in Louisiana

“We have laid our bridge twice, and it is in the river now about 12 miles down the river. When we laid it the first time, they was a fighting good all around us. They throwed them at a bridge about a 1/4 of a mile above us. It was shells they throwed, but they didn’t hurt us nor come anywhere near us. We could see both sides, the rebels and our men too, and I can tell you it was a sight to see.”

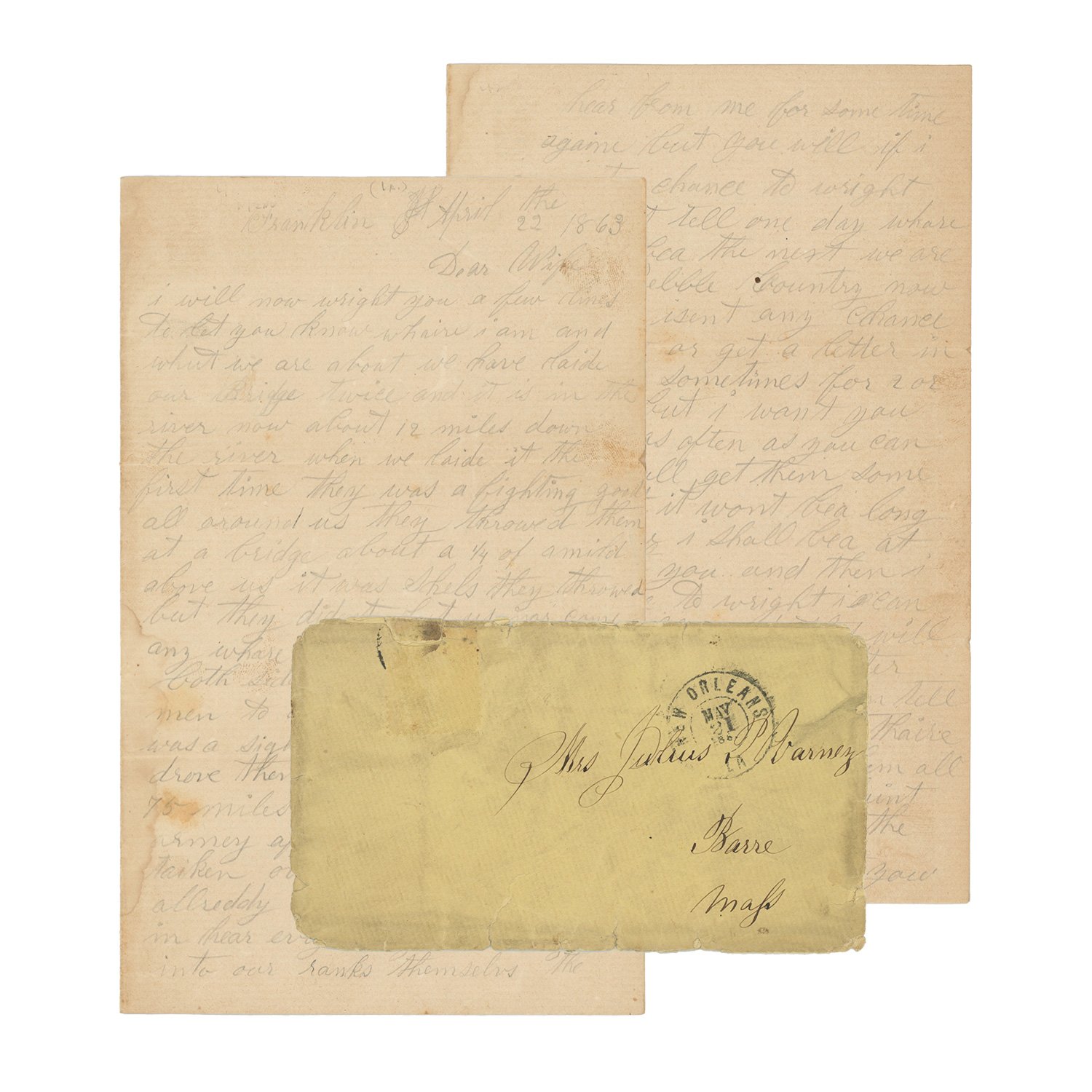

Item No. 2079499

This 8-page letter from April 1863 was written by Private Julius P. Varney to his wife at home in Barre, Massachusetts. Writing from Franklin, Louisiana, Varney recounts bridge-building amid shellfire, the capture of thousands of Confederate prisoners during the Bayou Teche Campaign, and the daily struggles of sickness and want far from home.

Varney was a member of Company K, 42nd Massachusetts Infantry—a nine-month unit assigned to the Department of the Gulf under the command of General Nathaniel P. Banks. Rather than serving together as a single unit, the 42nd had companies detailed to various duties. Varney and Company K were detailed as engineer troops in the 19th Corps, building pontoon bridges, repairing bridges, and clearing torpedoes and obstructions from waterways.

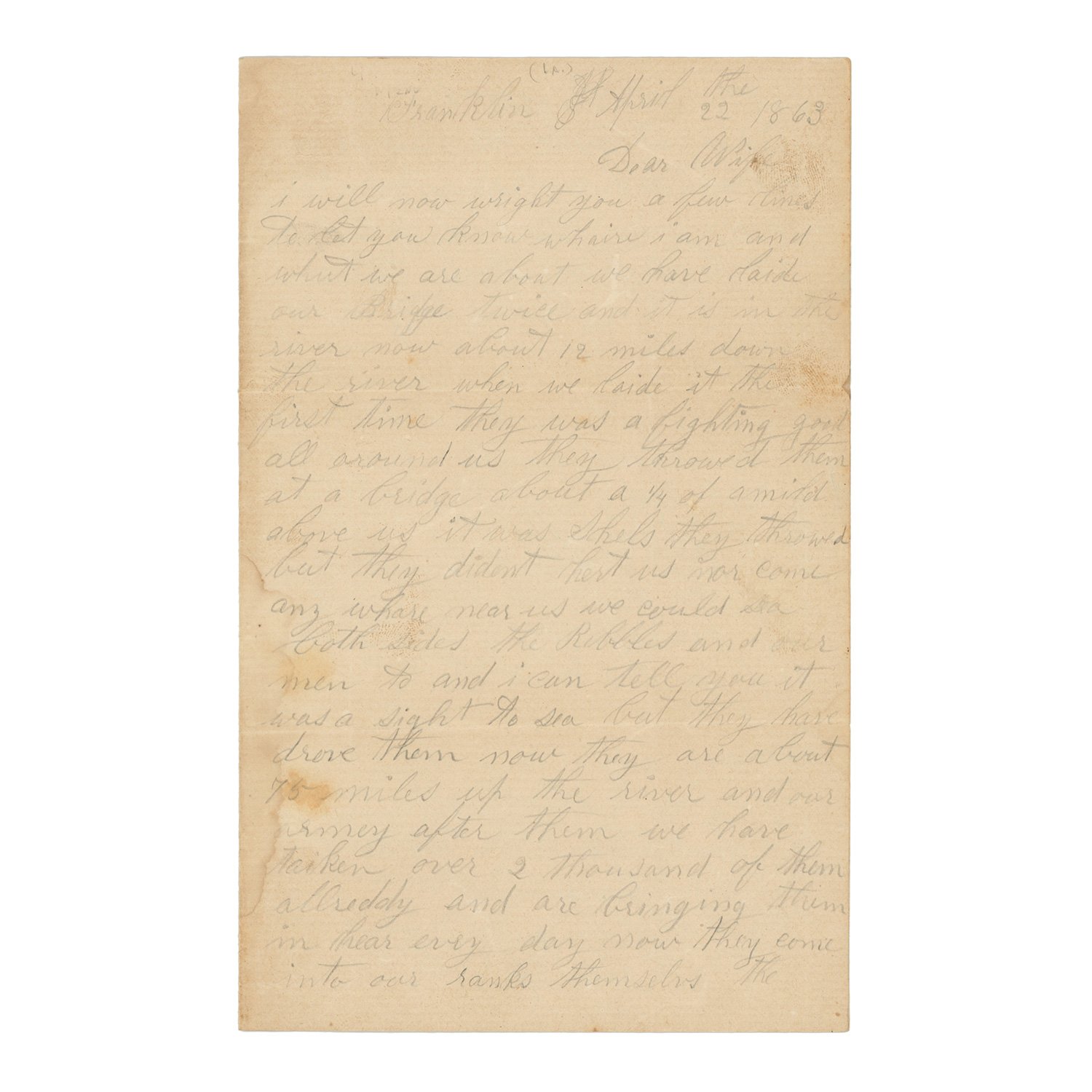

Varney gets right into it at the beginning of his letter, describing how, in support of Banks’s advance, the company laid the bridge across Bayou Teche near present-day Morgan City on April 9 and again near Pattersonville on April 13:

We have laid our bridge twice, and it is in the river now about 12 miles down the river. When we laid it the first time, they was a fighting good all around us. They throwed them at a bridge about a 1/4 of a mile above us. It was shells they throwed, but they didn’t hurt us nor come anywhere near us. We could see both sides, the rebels and our men too, and I can tell you it was a sight to see. But they have drove them now.

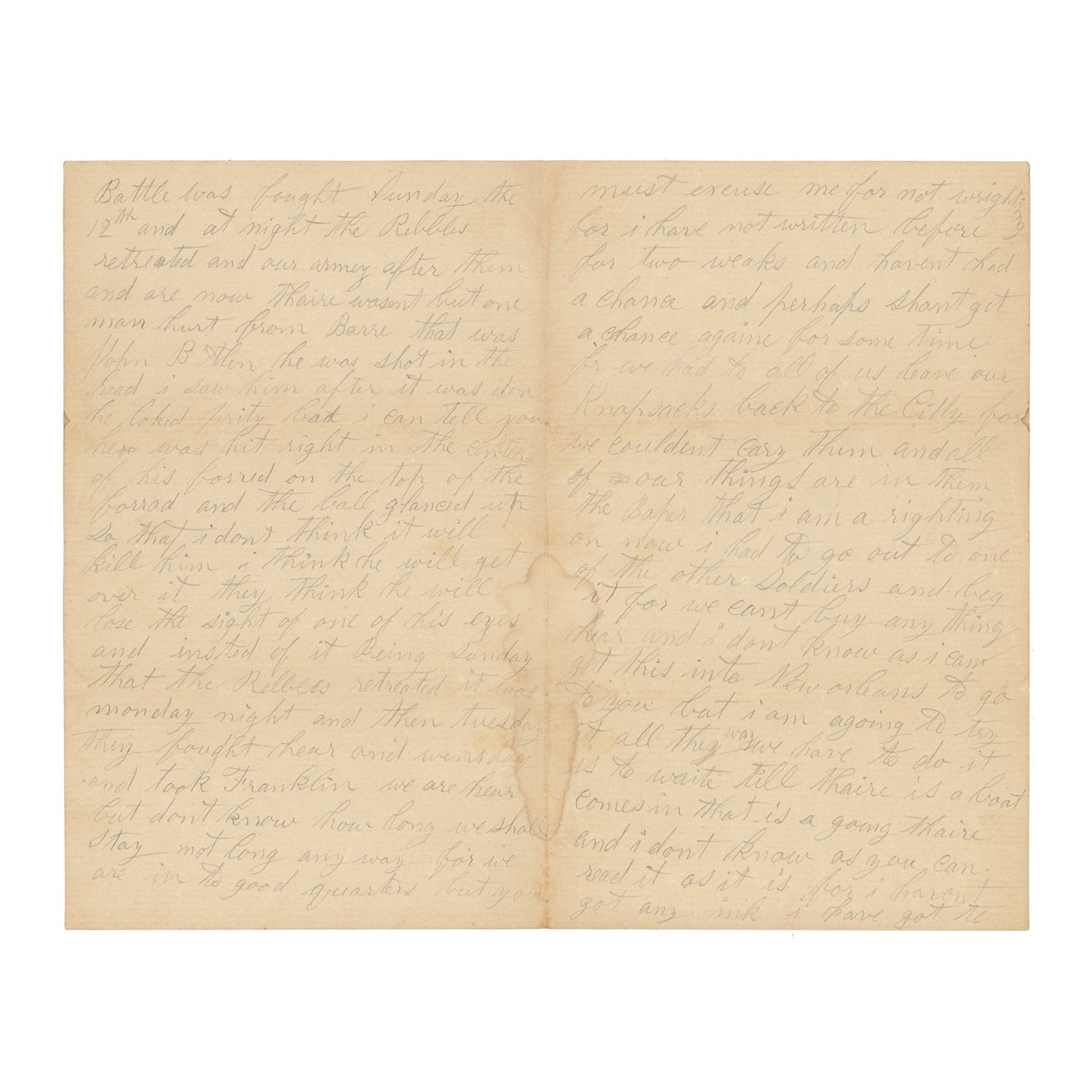

In a lengthy passage, Varney recounts the fighting at the Battle of Fort Bisland and the Battle of Irish Bend, noting the serious wounding of a comrade from Barre:

They are about 75 miles up the river, and our army after them. We have taken over 2 thousand of them already, and are bringing them in here every day now. They come into our ranks themselves. Battle was fought Sunday the 12th and at night the rebels retreated, and our army after them, and are now. There wasn’t but one man hurt from Barre. That was John P. Allen. He was shot in the head. I saw him after it was done. He looked pretty bad, I can tell you. He was hit right in the center of his forehead on the top of the forehead, and the ball glanced up so that I don’t think it will kill him. I think he will get over it. They think he will lose the sight of one of his eyes. And instead of it being Sunday that the rebels retreated, it was Monday night, and then Tuesday they fought here, and Wednesday, and took Franklin. We are here, but don’t know how long we shall stay.

Private John Allen, a 38-year-old farmer who served in the 53rd Massachusetts, had received his wound April 13 in the Fort Bisland fighting, but died at Berwick City on April 19.

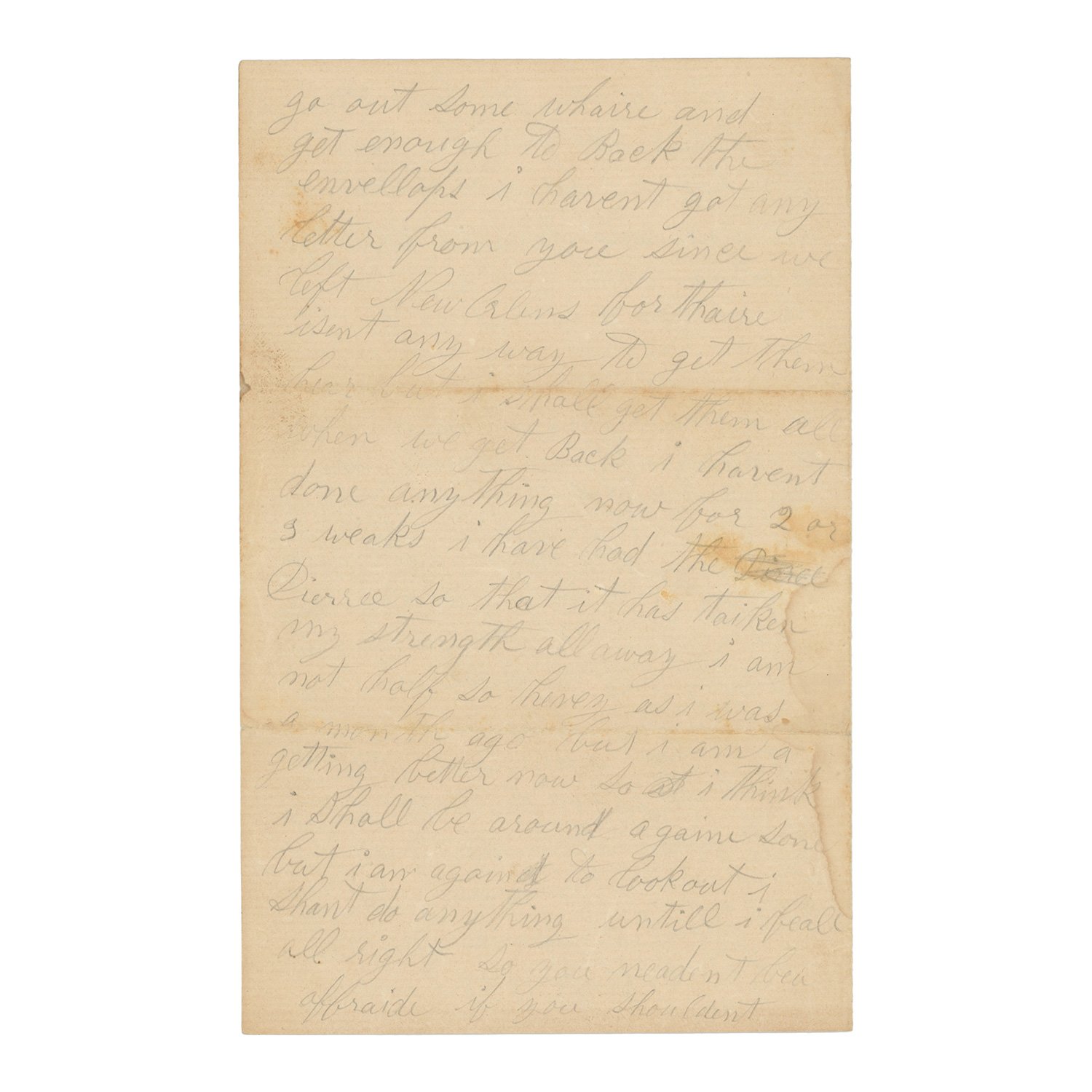

Beyond the battlefield, Varney writes candidly of privation and illness. Everything was in short supply while on campaign, particularly since they had been forced to leave their knapsacks in New Orleans. Even writing paper was scarce. “The paper that I am writing on now, I had to go out to one of the other soldiers and beg it,” he writes, “for we can’t buy anything here and I don’t know as I can get this into New Orleans to go to you.” He writes that he has also suffered with diarrhea through this time, “so that it has taken my strength all away.”

Despite hardship, he remains hopeful and affectionate, longing for his wife and child and looking forward to home. “It won’t be long now before I shall be at home with you,” he writes. “Oh, if I could be there now I would give them all they owe me.”

Near the end of his letter, Varney describes the beauty of the region:

This is one of the most splendid countries you ever saw here. The land is high here and level as a flare. And there is some splendid mansions here, I can tell you. When I get home, I will tell you all about it. I can’t find room to write it. And another thing, I han’t any hand to write such things as that I can talk it out better, so you can look out for a good long story when I get home.

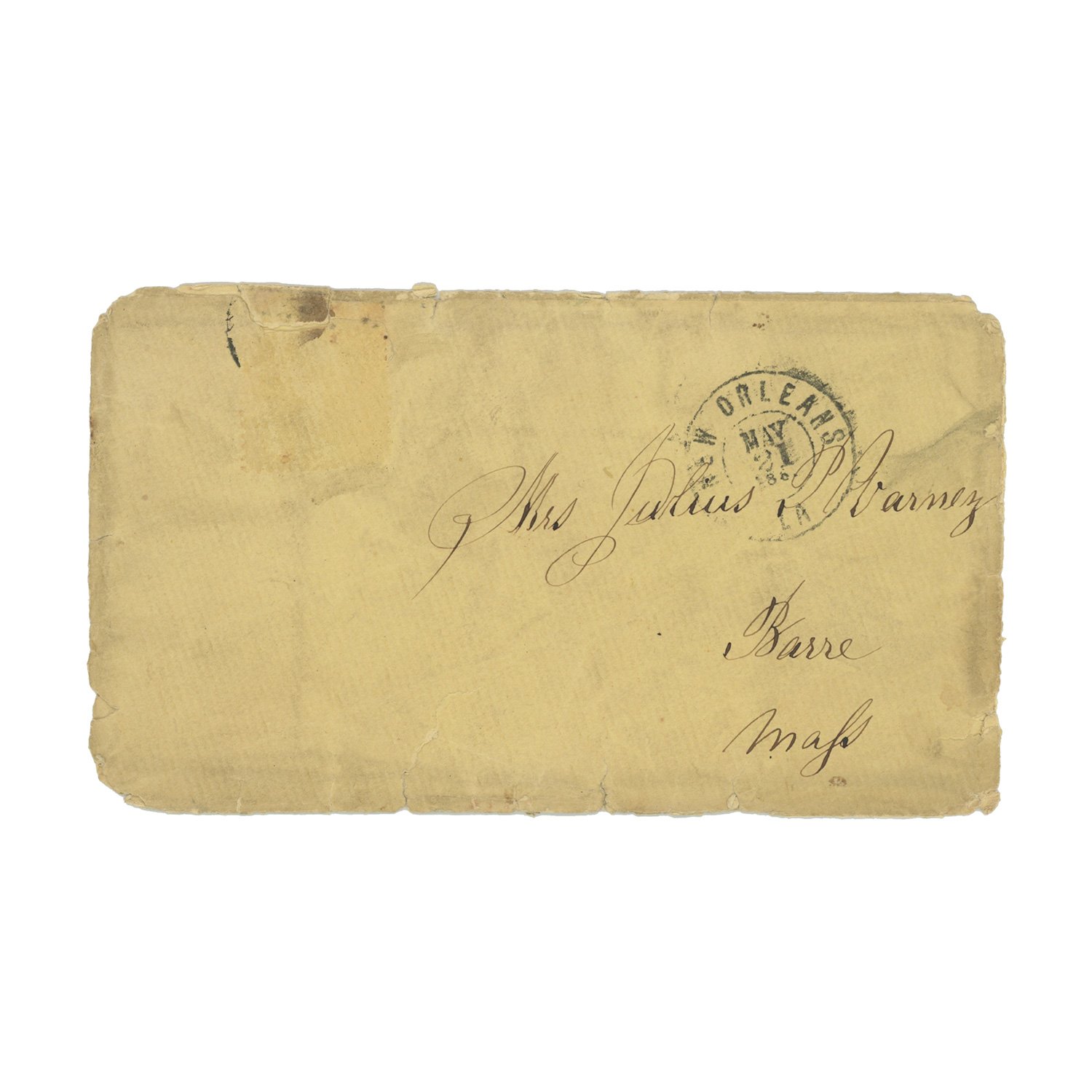

The letter was written upon 8 pages, covering two separate bifolium letter sheets each measuring about 5” x 8”. It is written in pencil because, as Varney explains, “I haven’t got any ink” and would have to “get enough to back the envelope.” The writing is faint, but legible. Varney wrote phonetically for many portions of his letter--which has been corrected in the transcript to aid in readability. Light foxing and toning are present. Creased at the original folds. Included is the original postal cover with New Orleans postmark. The full transcript of the letter can be read below.

Franklin, April the 22, 1863

Dear Wife

I will now write you a few lines to let you know where I am and what we are about. We have laid our bridge twice, and it is in the river now about 12 miles down the river. When we laid it the first time, they was a fighting good all around us. They throwed them at a bridge about a 1/4 of a mile above us. It was shells they throwed, but they didn’t hurt us nor come anywhere near us. We could see both sides, the rebels and our men too, and I can tell you it was a sight to see. But they have drove them now. They are about 75 miles up the river, and our army after them. We have taken over 2 thousand of them already, and are bringing them in here every day now. They come into our ranks themselves. Battle was fought Sunday the 12th and at night the rebels retreated, and our army after them, and are now. There wasn’t but one man hurt from Barre. That was John P. Allen. He was shot in the head. I saw him after it was done. He looked pretty bad, I can tell you. He was hit right in the center of his forehead on the top of the forehead, and the ball glanced up so that I don’t think it will kill him. I think he will get over it. They think he will lose the sight of one of his eyes. And instead of it being Sunday that the rebels retreated, it was Monday night, and then Tuesday they fought here, and Wednesday, and took Franklin. We are here, but don’t know how long we shall stay. Not long, anyway, for we are in too good quarters.

But you must excuse me for not writing, for I have not written before for two weeks and haven’t had a chance, and perhaps shan’t get a chance again for some time, for we had to all of us leave our knapsacks back to the city, for we couldn’t carry them. And all our things are in them. The paper that I am writing on now, I had to go out to one of the other soldiers and beg it, for we can’t buy anything here and I don’t know as I can get this into New Orleans to go to you. But I am a going to try it. All the way we have to do it is to wait till there is a boat comes in that is a going there, and I don’t know as you can read it as it is, for I haven’t got any ink. I have got to go out somewhere and get enough to back the envelopes. I haven’t got my letter from you since we left New Orleans, for there I sent any way to get them here, but I shall get them all when we get back.

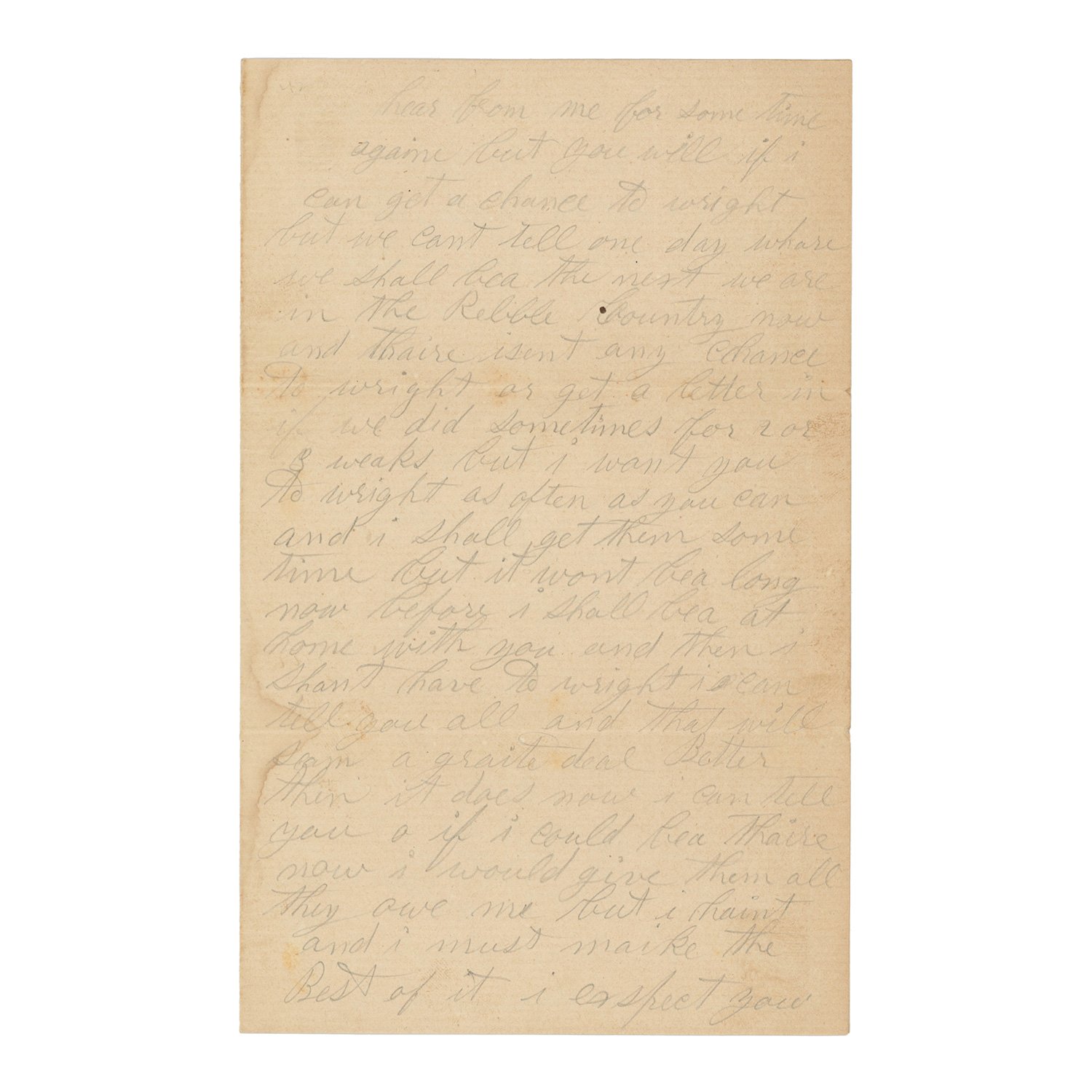

I haven’t done anything now for 2 or 3 weeks. I have had the diarrhea so that it has taken my strength all away. I am not half so heavy as I was a month ago, but I am a getting better now, so I think I shall be around again soon. But I am a going to look out. Shan’t do anything until I feel all right. So you needn’t be afraid if you shouldn’t hear from me for some time again. But you will if I can get a chance to write. But we can’t tell one day where we shall be the next. We are in the rebels’ country now, and there isn’t any chance to write, or get a letter in if we did, sometimes for 2 or 3 weeks. But I want you to write as often as you can and I shall get them some time. But it won’t be long now before I shall be at home with you. And then I shan’t have to write. I can tell you all, and that will seem a great deal better than it does now, I can tell you. Oh, if I could be there now I would give them all they owe me. But I hain’t and I must make the best of it.

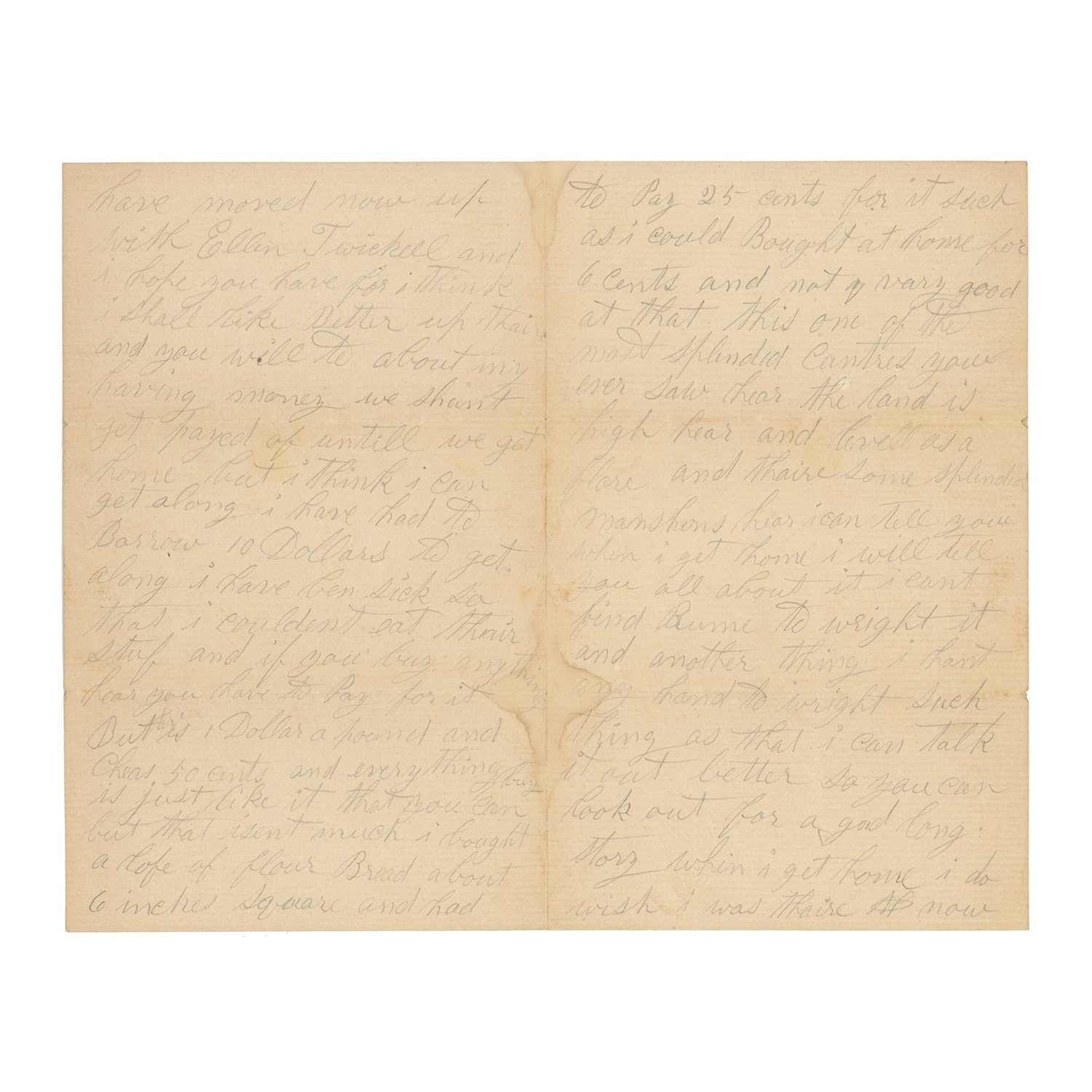

I expect you have moved now up with Ellen Twickell, and I hope you have, for I think I shall like better up there, and you will too. About my having money, we shan’t get paid off until we get home. But I think I can get along. I have had to borrow 10 dollars to get along. I have been sick so that I couldn’t eat their stuff. And if you buy anything here, you have to pay for it. Butter is 1 dollar a pound and cheese 50 cents, and everything is just like it that you can, but that I sent much I bought a loaf of flour bread about 6 inches square and had to pay 25 cents for it, such as I could bought at home for 6 cents, and not very good at that.

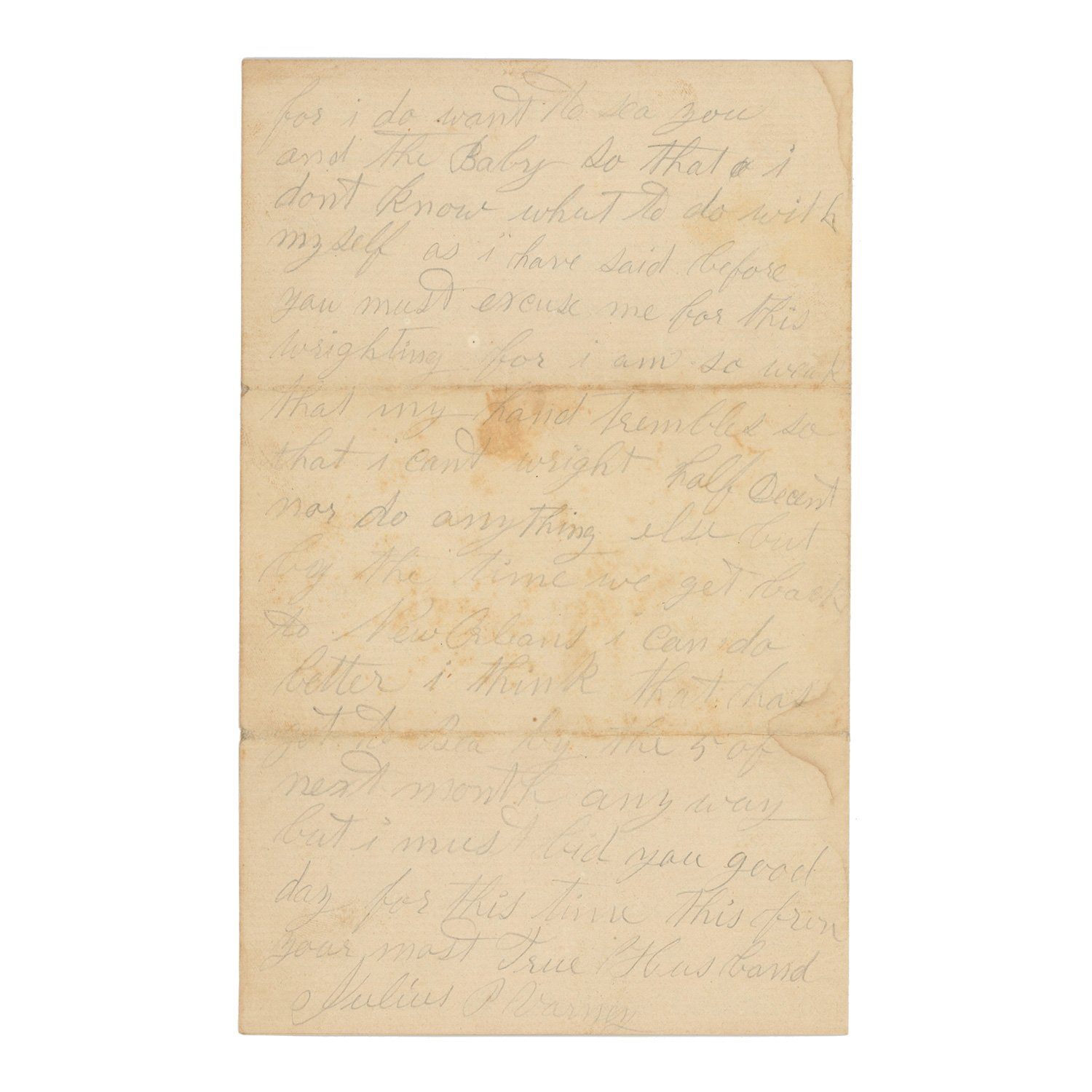

This is one of the most splendid countries you ever saw here. The land is high here and level as a flare. And there is some splendid mansions here, I can tell you. When I get home, I will tell you all about it. I can’t find room to write it. And another thing, I han’t any hand to write such things as that I can talk it out better, so you can look out for a good long story when I get home. I do wish I was there now, for I do want to see you and the baby so that I don’t know what to do with myself. As I have said before, you must excuse me for this writing, for I am so weak that my hand trembles so that I can’t write half decent, nor do anything else. But by the time we get back to New Orleans, I can do better I think. That has got to be by the 5 of next month anyway. But I must bid you good day for this time. This from your most True Husband

Julius P. Varney