1864 Letter by Colonel William C. Cooper, 142nd Ohio — Regiment Attached to 10th Corps at Bermuda Hundred — "have been in the front of both Grant’s & Butler’s army without being in any exposed danger"

1864 Letter by Colonel William C. Cooper, 142nd Ohio — Regiment Attached to 10th Corps at Bermuda Hundred — "have been in the front of both Grant’s & Butler’s army without being in any exposed danger"

Item No. 3865758

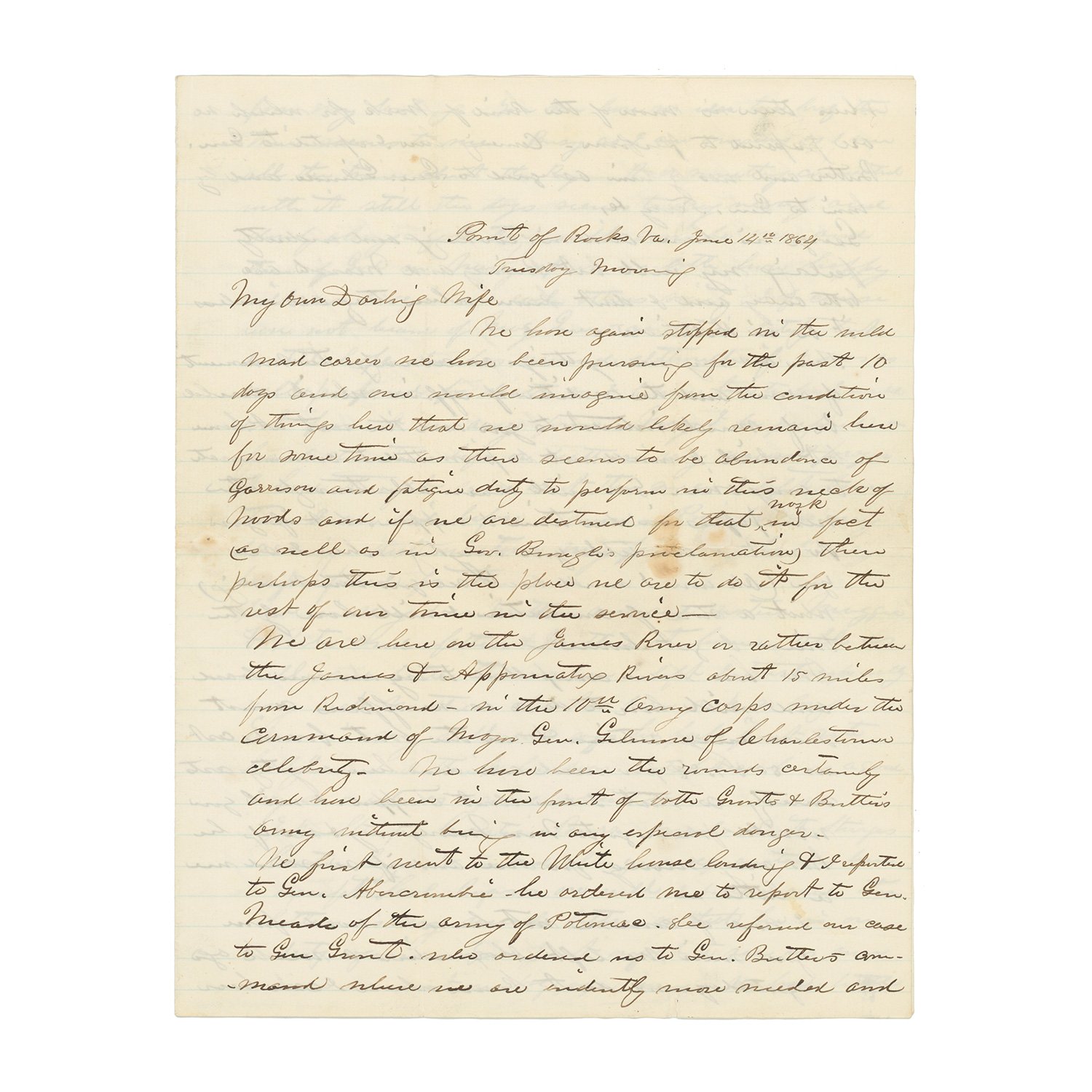

An interesting wartime letter written by Colonel William C. Cooper of the 142nd Ohio Volunteer Infantry, composed from Point of Rocks, Virginia, June 14, 1864, while serving under Major General Quincy A. Gillmore’s 10th Corps during the Bermuda Hundred Campaign. Writing to his wife Eliza Russell Cooper, the colonel discusses his regiment’s movements between General Ulysses S. Grant’s and General Benjamin F. Butler’s armies, the hardships of campaign life, and his deep feelings of longing and faith amid the war’s uncertainty.

Cooper opens the letter discussing the regiment’s latest status. “We have again stopped in the wild mad career we have been pursuing for the past 10 days,” he writes, “and one would imagine from the condition of things here that we would likely remain here for some time, as there seems to be an abundance of Garrison and fatigue duty to perform in this neck of the woods.” He further states that if that sort of work can be expected, “then perhaps this is the place we are to do it for the rest of our time in the service.”

The 142nd Ohio was a short-term regiment organized in May 1864 for 100 days’ service. Assigned to the Army of the James, the unit performed essential garrison and picket duties during Butler’s operations south of Richmond, helping to secure supply lines and river crossings.

Cooper continues, noting that their location is “between the James & Appomattox Rivers, about 15 miles from Richmond—in the 10th Army Corps under the command of Major Gen. Gillmore of Charleston celebrity.” Quincy A. Gillmore had commanded Union forces operation against Charleston the previous summer. “We have been the rounds,” Cooper adds, “and have been in the front of both Grant’s & Butler’s army without being in any exposed danger.”

He then relates how upon the regiment’s arrival at White House Landing, he reported to General Abercrombie, who referred him to General Meade, then to Grant, then to Butler, “and was by him assigned to Gen. Gillmore, and by him to Gen. Terry.”

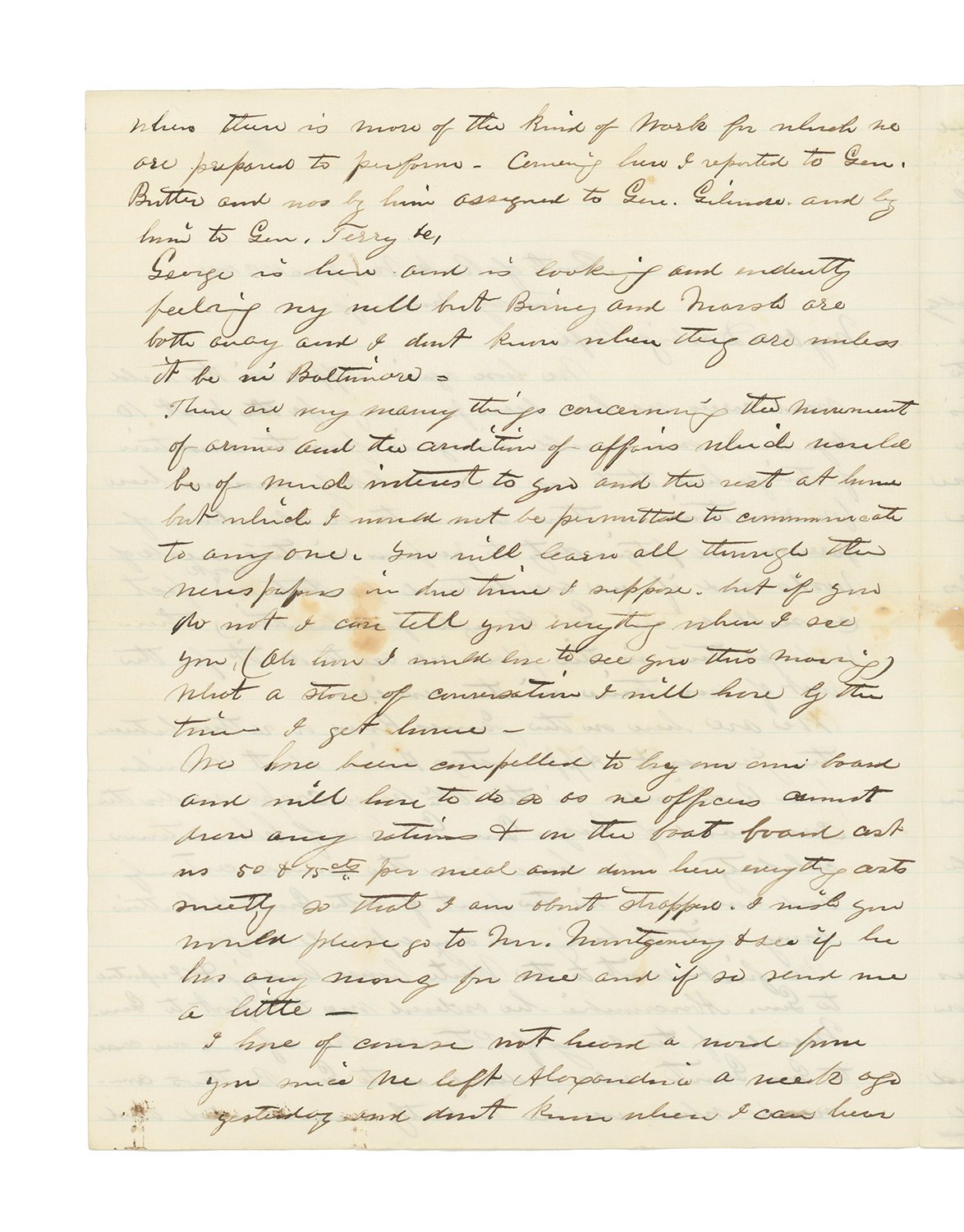

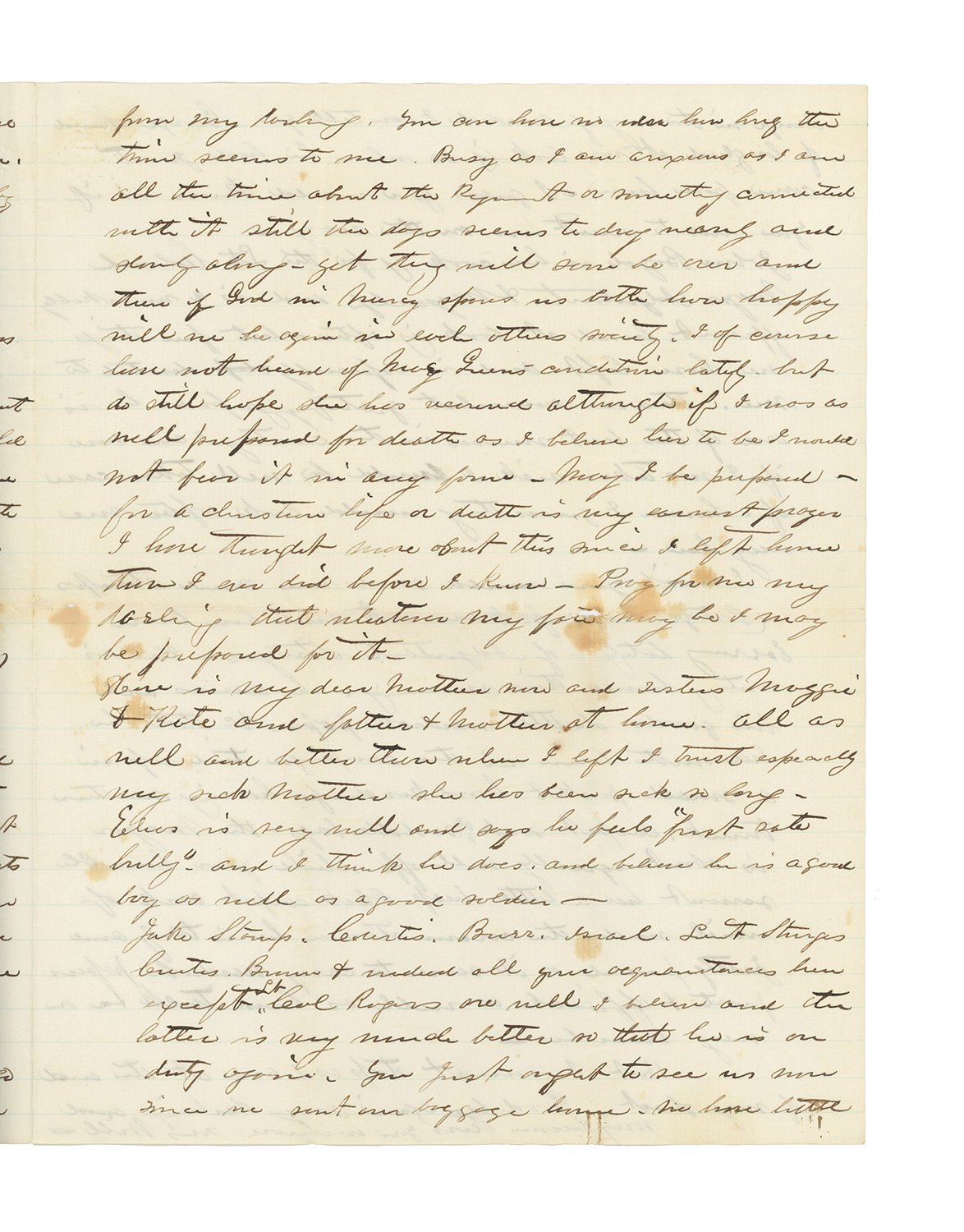

Cooper’s voice alternates between the practical and the poignant—complaining of high prices, the need to “buy our own board,” and the absence of rations for officers—yet his affection for his wife shines throughout. He speaks tenderly of home, of his mother’s illness, and of renewed spiritual reflection brought on by the hardships of the campaign. “May I be prepared for a Christian life or death is my very earnest prayer,” he declares, adding, “I have thought more about this since I left home than I ever did before.” In a later passage, he writes:

You can have no idea how long the time seems to me. Busy as I am, anxious as I am all the time about the Regiment or something connected with it. Still, the days seem to drag along and slowly along—yet they will soon be over. And then if God in mercy spares us both, how happy will we be again in each other’s society.

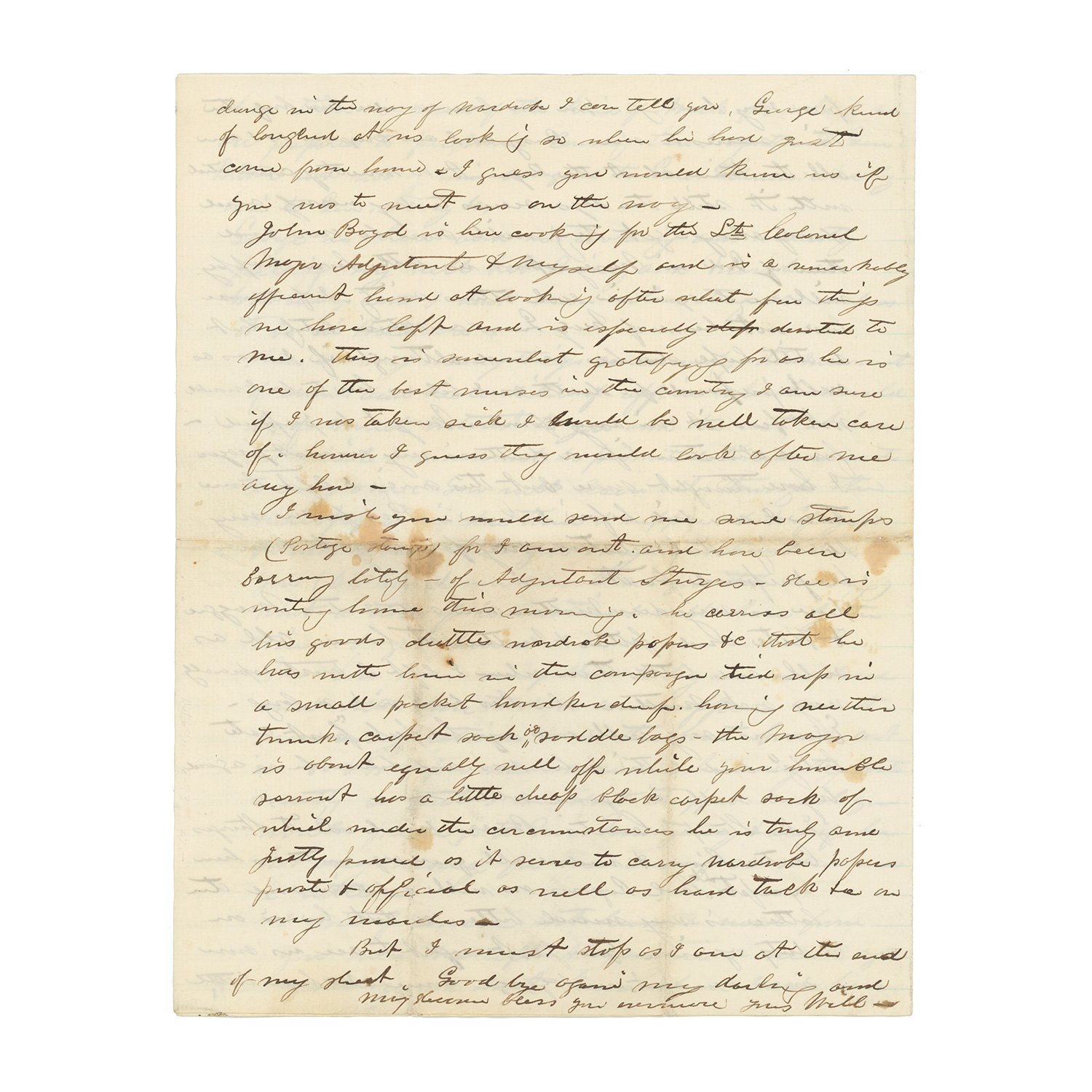

Near the letter’s conclusion, Cooper adds domestic details of fellow officers from the regiment, including Lieutenant Colonel William Rogers, Assistant Surgeon Jake Stamp, Lieutenant Lucian B. Curtis, and others. Remarking how their baggage had been sent home, Cooper notes, “We have little change in the way of wardrobe, I can tell you. George kind of laughed at us looking so when we had just come from home. I guess you would know us if you were to meet us on the way.”

He closes observing how Adjutant Frederick D. Sturges “carries all his goods, letters, wardrobe, papers, &c. that he has with him in the campaign tied up in a small pocket handkerchief, having neither trunk, carpet sack, or saddle bags.” Comparatively, he states that “the Major is about equally well off, while your humble servant has a little cheap black carpet sack of which…serves to carry wardrobe, papers private & official, as well as hard tack, &c., and my swords.”

Cooper had gained experience earlier in the war as an officer in the 4th Ohio Volunteers. After the war, he returned to his native Mount Vernon, Ohio, and resumed his law practice. He entered public service as a state legislator (1872-74) and later served as Ohio’s Judge Advocate General (1879-84). In 1885 he was elected to three consecutive terms in the U.S. House of Representatives, serving until 1891. Following his congressional service he returned to private law practice and remained a respected civic leader until his death on August 29, 1902.

The letter was written on four pages of a bifolium letter sheet measuring about 7 3/4” x 9 3/4”. Light foxing and toning. Creased at the original folds. The full transcript appears below.

Point of Rocks Va. June 14th 1864

Tuesday Morning

My Own Darling Wife

We have again stopped in the wild mad career we have been pursuing for the past 10 days, and one would imagine from the condition of things here that we would likely remain here for some time, as there seems to be an abundance of Garrison and fatigue duty to perform in this neck of the woods. And if we are destined for that work in fact (as well as in Gov. Brough’s proclamation) then perhaps this is the place we are to do it for the rest of our time in the service.

We are here on the James River, or rather between the James & Appomattox Rivers, about 15 miles from Richmond—in the 10th Army Corps under the command of Major Gen. Gillmore of Charleston celebrity. We have been the rounds, certainly, and have been in the front of both Grant’s & Butler’s army without being in any exposed danger.

We first went to the White house landing & I reported to Gen. Abercrombie. He ordered me to report to Gen. Meade of the Army of the Potomac. He referred our case to Gen. Grant, who ordered us to Gen. Butler’s command, where we are evidently more needed and where there is more of the kind of work for which we are prepared to perform. Coming here, I reported to Gen. Butler and was by him assigned to Gen. Gillmore, and by him to Gen. Terry, &c.

George is here and is looking and evidently feeling very well, but Birney and Marsh are both away and I don’t know where they are unless it be in Baltimore.

There are very many things concerning this movement of armies and the condition of affairs which would be of much interest to you and the rest at home, but which I would not be permitted to communicate to anyone. You will learn all through the newspapers in due time, I suppose. But if you do not, I can tell you everything when I see you. (Oh how I would love to see you this morning.) What a store of conversation I will have by the time I get home.

We have been compelled to buy our own board, and will have to do so as we officers cannot draw any rations. & on the boat, board cost us 50 & 75 cts per meal, and down here everything costs mostly so that I am about strapped. I wish you would please go to Mr. Montgomery & see if he has any money for me, and if so, send me a little.

I have, of course, not heard a word from you since we left Alexandria a week ago yesterday and don’t know when I can hear from my darling. You can have no idea how long the time seems to me. Busy as I am, anxious as I am all the time about the Regiment or something connected with it. Still, the days seem to drag along and slowly along—yet they will soon be over. And then if God in mercy spares us both, how happy will we be again in each other’s society. I, of course, have not heard of Mary Jean’s condition lately, but do still hope she has recovered. Although, if I was as well prepared for death as I believe her to be, I would not fear it in any form. May I be prepared for a christian life or death is my very earnest prayer. I have thought more about this since I left home than I ever did before, I know. Pray for me, my darling, that whatever my fate may be, I may be prepared for it.

How is my dear mother now, and sisters Maggie & Kate, and father & mother at home? All as well and better than when I left, I trust, especially my sick mother. She has been sick so long. Elias is very well and says he feels “first rate bully,” and I think he does, and believe he is a good boy as well as a good soldier.

Jake Stamp, Curtis, Burr, Israel, Lieut. Surges, Curtis Brown, & indeed all your acquaintances here except Lt. Col. Rogers are well, I believe, and the latter is very much better so that he is on duty again. You just expect to see us now since we sent our baggage home. We have little change in the way of wardrobe, I can tell you. George kind of laughed at us looking so when we had just come from home. I guess you would know us if you were to meet us on the way.

John Boyd is here cooking for the Lt. Colonel, Major, Adjutant, & myself, and is a remarkably efficient hand at looking after what few things we have left, and is especially devoted to me. This is somewhat gratifying, for he is one of the best nurses in the country. I am sure if I was taken sick I would be well taken care of. However, I guess they would look after me anyhow.

I wish you would send me some stamps (Postage stamps) for I am out and have been borrowing lately of Adjutant Sturges. He is writing home this morning. He carries all his goods, letters, wardrobe, papers, &c. that he has with him in the campaign tied up in a small pocket handkerchief, having neither trunk, carpet sack, or saddle bags. The Major is about equally well off, while your humble servant has a little cheap black carpet sack of which, under the circumstances, he is truly and justly [illegible], as it serves to carry wardrobe, papers private & official, as well as hard tack, &c., and my swords.

But I must stop, as I am at the end of my sheet. Goodbye again, my darling, and may Heaven bless you evermore.

Yours, Will