Archive of Letters by Private DeWitt C. Ormsbee, 1st Vermont Heavy Artillery — Battles of Winchester and Fisher's Hill — Burning of the Shenandoah Valley — Rebels Use Colored Troops at Petersburg

Archive of Letters by Private DeWitt C. Ormsbee, 1st Vermont Heavy Artillery — Battles of Winchester and Fisher's Hill — Burning of the Shenandoah Valley — Rebels Use Colored Troops at Petersburg

Item No. 8730089

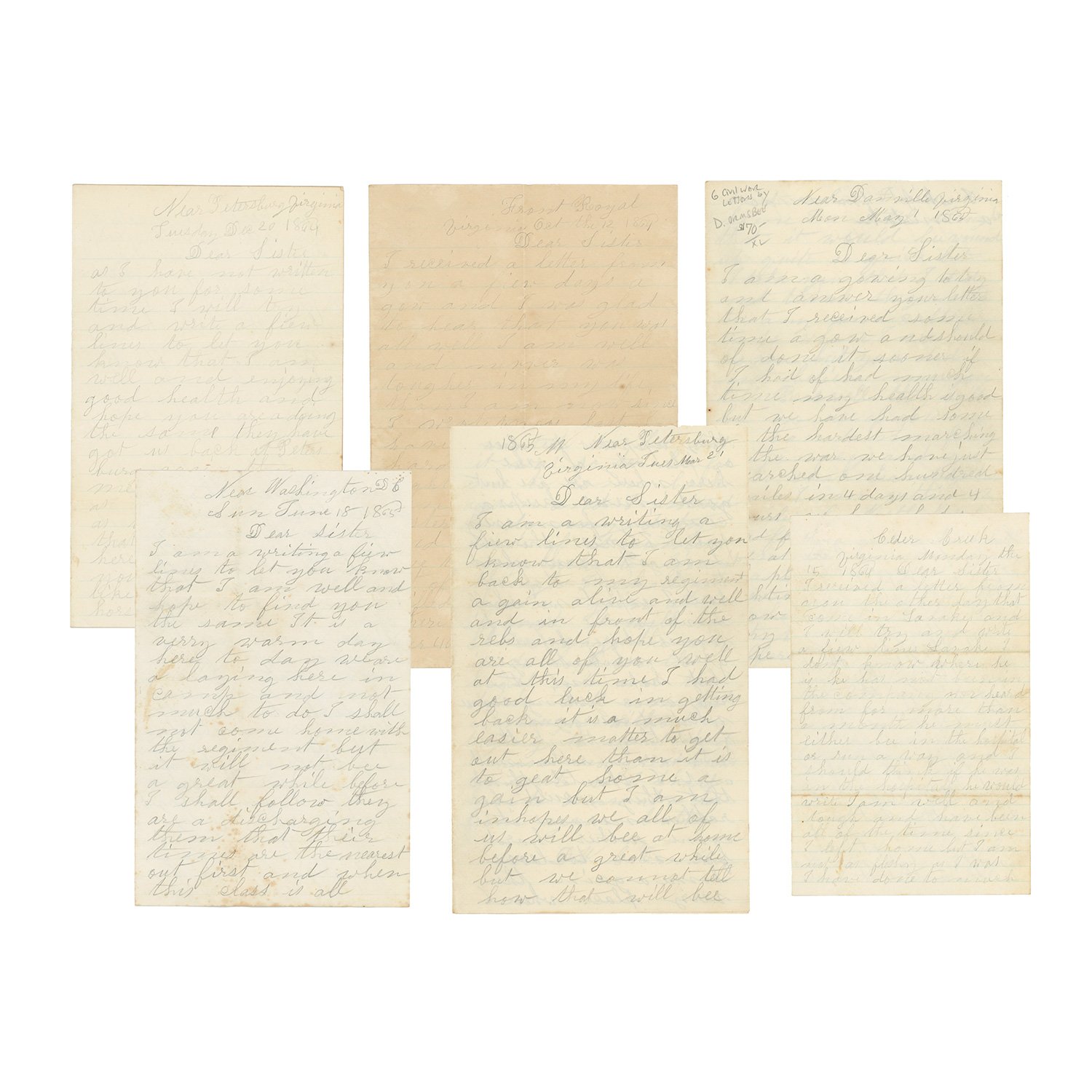

This archive includes six letters written by Private DeWitt C. Ormsbee of the 1st Vermont Heavy Artillery between August 1864 and June 1865. In the letters Ormsbee discusses topics that include hard marching, desertion, the Battle of the Weldon Railroad, the Battle of Winchester, the Battle of Fisher’s Hill, the burning of the Shenandoah Valley, the rebels’ use of colored troops at Petersburg, and more.

In July 1864 Ormsbee and his comrades traveled from Petersburg to Washington, rushed north as reinforcements when Confederate General Jubal Early threatened the Capitol. Early was then defeated at Fort Stevens, and on July 13 retreated back into Virginia. To deal with Early, in early August General Ulysses S. Grant consolidated several military departments and placed them under the command of General Philip H. Sheridan. It became Sheridan’s task to pursue Early into the Shenandoah Valley and to close the region as a source of supplies for the Confederates.

The first letter was written August 15, 1864, from Cedar Creek, Virginia. Ormsbee opens by stating that a friend, Lavake Ainsworth, “has not been in the company, nor heard from, for more than a month,” adding that, “He must either be in the hospital or run away, and I should think if he was in the hospital he would write.” Ainsworth is listed in HDS as having deserted July 26. Continuing his letter, Ormsbee writes:

I am well and tough and have been all of the time since I left home, but I am not as fleshy as I was. I have done too much hard marching to be fat. It don’t seem as if a man could stand what they have to here, but they will stand more than I ever thought they could. There has been more fighting and marching this campaign than there had been in the whole war before. We have marched and carried our loads right through all of this hot weather, and they have always before laid still in the hot weather. I have seen them melted and sun struck in these hot marches so thick that it is worse than a quite a hard battle. There was so many such doings as that—is nothing but right out murder.

Continuing his tirade, he turns his ire toward the 1st Vermont’s officers, whom he considers responsible for the loss of so many men captured June 23 at the First Battle of the Weldon Railroad:

The officers will drink their whiskey and ride on a horse and rush their men with heavy loads in the intense hot sun. We lost 350 men taken prisoners out of our regiment at one time just by whiskey and drunken officers. Damn such officers, and we have too many of just such ones as they won’t allow the privates to have a drop. There was a drink issued to the men 3 times and that was all, and there was not enough of that to wet a dish and if the officers did not have any more the country would be better off.

By the time Ormsbee wrote his second letter, Sheridan’s army had already won a victory at Winchester on September 19, forcing Early to retreat to Fisher’s Hill near Strasburg, where Sheridan was again victorious September 21-22. Early retreated far to the south. From Front Royal on October 12 Ormsbee writes of the fighting:

Since I wrote to you last I have been in some hard battles—the hardest fighting that I have seen. The Battle of Winchester was the 19 of Sept and it was a hard one, to we lost 97 men out of our regiment killed and wounded there, and there wasn’t over 400 men in the regiment that was in the fight. The bullets come as thick as hail and mowed us terribly. We were in the center and right in front of the rebs’ artillery, and they sent the shells among us like torpedoes. But we drove them handsomely, and they fell back to Strasburg and made another stand. We attacked them the 21 and had a 2 days fight, and drove them again, and chased them about 3 days and nights. We got about 40 pieces of artillery away from them and their army was dreadfully demoralized. They have always whipped our army here in the valley before, but we have just whipped them out now. But we lost some brave boys to show the mark.

He writes skeptically, “There is some good news here from Petersburg and Richmond if it is true. It is reported that Old Grant has taken Petersburg. But I am dreadful afraid that it ain’t true. But I hope that he has done the job, for I don’t ever want to see that place again.”

With Early in retreat, Sheridan was free to execute the second part of his orders. In doing so he laid waste to practically the entire area from Staunton to Harrisonburg. At the conclusion of the second letter Ormsbee writes, “The Army makes things look desolate here in the valley, destroy about everything they can get hold of.”

In the third letter dated December 20 from near Petersburg, Ormsbee writes:

They have got us back at Petersburg again. They mean to keep us as near the rebs as they can, and that is pretty near to here. I can tell you it is some like driving a free horse to death with this corps. It is called the best fighting corps in the army, and they mean to keep it where there is a plenty of it to do, but the rebs have not fared very well this season, for they have been worsted in every point. There is a great many comes into our lines here, but I had rather be a little farther from them. But they are not very quarrelsome just now, but they are liable to be at any time.

He closes this letter writing to his sister, “I did not think you was a going to raising up soldiers, but I guess the war will end before they will get large enough to come out here. At any rate, I hope so.” He concludes that the reels “cannot always hold out in the way they have gone this year.”

The fourth letter was written March 21, 1865, from the Petersburg lines. Just returned from a furlough, Ormsbee yearns to be back home, while discussing the rebels’ chances and their anecdotal use of colored troops:

I am a writing a few lines to let you know that I am back to my regiment again, alive and well, and in front of the rebs… There appears to be a plenty of rebs here where we are, but good news keeps a coming from every point. I guess the rebs have got some colored troops in front of us here. I expect we shall have some rough times here before a great while longer, but hope not. The rebs are a getting somewhat discouraged. I guess they think their chance is rather small and I should think that they would be rather nervous. It came rather hard for me to leave home again—the very place where I wanted to be, but it was so to be for me to come back again, and I intend to do my duty. And if it comes my luck to live it through I shall get home again, and if not it will be other ways. The way is to look on the bright side and the dark will come fast enough without trying to see it ahead.

Ormsbee wrote the fifth letter from Danville on May 1, 1865, as the conflict was wrapping up. After Lee’s surrender at Appomattox in April, the 6th Corps had just completed a long march to Danville in pursuit of rebel holdouts. He writes:

My health is good, but we have had some of the hardest marching of the war. We have just marched one hundred miles in 4 days and 4 hours. We have had some hard fighting since I was at home, but it has all played out now. The fighting all over with now and I ain’t any sorry, and I hope that anyone else ain’t. When I was at home I a little thought that it would be wound up quite so quick but I told you that I did not think they would be any more calls for troops when I was at home but you did not believe me. You tell Roswell there will be no use of going to Canada now for the journey, and we can shake hands together.

He continues:

Now I am within 2 miles of North Carolina, the farthest I ever have been from home. It is a splendid country here corn large enough to ho wheat all headed out that is some different from Vermont, but still it is not home, but if I am prospered with health I think I shall see promotion again in the course of time. You can a little imagine the feelings among the soldiers now, but I think the days ware off more slow now than they did before the fighting was over, for now I am anxious to get home and before I did not expect it and was contented with my lot, and looked for the worst and hoped for the best.

Ormsbee’s sixth letter was written from Washington on June 18 as he awaits his discharge:

I have done some hard marching since I last wrote to you, but I feel now that I have seen already my hardest times out here, for I probably will lay around in the vicinity of where we are now until I am discharged, and I am ready to see that time as son as they see fit to discharge us.

Ormsbee would be mustered out August 25, 1865, at Washington, DC.

The letters each are 3-4 pages and written in pencil upon letter sheets measuring about 5” x 8” and smaller. Some fading to the writing in a couple of the letters, but everything is legible. Letters are variously toned with some foxing. Creased at the original folds. The full electronic transcripts will be available to the buyer.